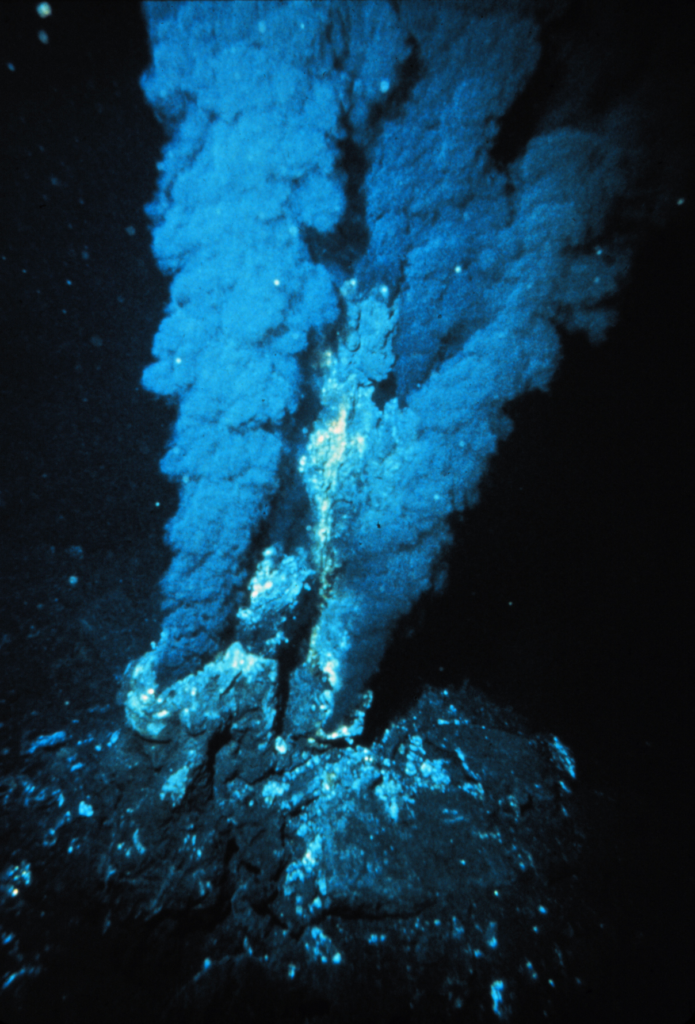

Volcano sharks living inside an active underwater volcano are not fiction. Recent satellite images confirm that Kavachi volcano—often called the “sharkcano” or even “sharkano”—is erupting again in the southwest Pacific. Despite superheated, acidic water and explosive activity, sharks and fish continue to inhabit its crater. The phenomenon of kavachi volcano sharks challenges assumptions about marine survival in extreme environments.

NASA’s Landsat 9 satellite captured images of the submarine eruption, showing a green plume rising through dark ocean waters. The plume marks superheated water, particulates and volcanic gases escaping from the volcano’s vent.

What Is the Shark Volcano Known as Kavachi?

Kavachi volcano lies roughly 15 miles south of Vangunu Island in the Solomon Islands, east of Papua New Guinea. It is one of the most active submarine volcanoes in the Pacific.

Named after a sea god revered by the Indigenous Gatokae and Vangunu communities, Kavachi has erupted frequently since at least 1939. Local islanders first documented activity in that year. Scientific records maintained by the Smithsonian’s Global Volcanism Program confirm nearly continuous eruptive behavior.

The volcano’s summit sits about 65 feet below the ocean surface. Its base rests on the seafloor approximately three-fourths of a mile beneath sea level. These dimensions explain why eruptions are primarily underwater, though activity sometimes breaches the surface.

NASA Observations and the Latest Eruption

The recent eruption was recorded by NASA’s Operational Land Imager-2 aboard Landsat 9. Satellite imagery revealed a vivid, greenish cloud spreading across surrounding waters.

This coloration results from heated water, dissolved minerals, sulfur compounds and volcanic debris. Such plumes can temporarily alter local water chemistry and visibility.

NASA previously documented eruptions in 2007 and 2014. Continued monitoring reflects the volcano’s persistent activity pattern rather than a singular event.

The shark volcano’s behavior remains dynamic, with activity levels fluctuating over months and years.

Why Is It Called Sharkcano or Sharkano?

The term sharkcano emerged after a 2015 scientific expedition discovered sharks living within Kavachi’s crater. Researchers used baited drop cameras to observe marine life in conditions considered hostile to most species.

They recorded scalloped hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna lewini) and silky sharks (Carcharhinus falciformis). The finding led to widespread interest in volcano sharks, lava sharks and the broader concept of shark volcano ecosystems.

The nickname “sharkano” gained popularity online, reflecting public fascination with the idea of predators inhabiting a volcanic vent.

Yet the discovery was grounded in methodical observation rather than myth.

Life Inside the Kavachi Volcano Sharks’ Habitat

Kavachi’s crater contains superheated and acidic water. Periodic eruptions release steam, lava fragments and sulfur-rich gases. Despite this, the 2015 expedition documented not only sharks but also reef fish and microbial communities.

Scientists described the site as a “natural laboratory.” The presence of volcano sharks suggests that certain marine species may tolerate rapid environmental shifts better than previously assumed.

Researchers noted gelatinous zooplankton and other organisms inhabiting the area. This biodiversity under extreme stress raises questions about adaptive capacity.

Table: Key Characteristics of the Shark Volcano Kavachi

Feature | Measurement | Significance

Distance from Vangunu Island | ~15 miles | Regional location

Summit depth | ~65 feet below surface | Near-surface eruption potential

Base depth | ~0.75 miles below sea level | Deep structural foundation

Documented eruptions | Since 1939 | Long-term activity

These data points contextualize the environment where kavachi volcano sharks persist.

Formation of Temporary Islands

Kavachi has occasionally produced ephemeral islands through eruptions. These landforms have reached lengths of up to one kilometer.

However, ocean waves quickly erode them. The islands are temporary, formed by volcanic debris and ash that lacks structural permanence.

Such cycles illustrate the volcano’s geomorphological volatility. The sharkcano is not a static structure but an evolving feature shaped by ongoing eruptions.

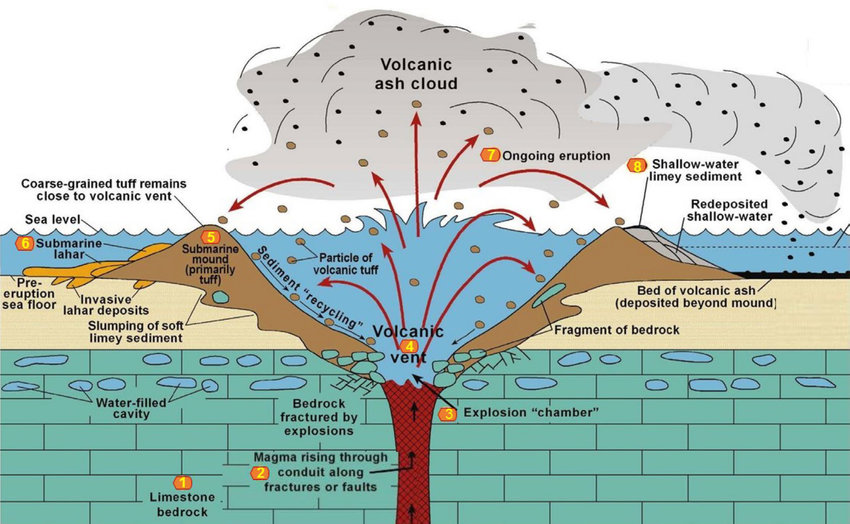

Phreatomagmatic explosions—caused by interaction between magma and seawater—can be particularly dramatic. These interactions generate steam-driven blasts that propel ash and rock fragments upward.

How Do Lava Sharks Survive Extreme Conditions?

The survival of lava sharks, or volcano sharks, remains a subject of active inquiry. Scientists propose several hypotheses:

- Sharks may enter the crater during quieter intervals between eruptions.

- Some species may tolerate short-term exposure to elevated temperature and acidity.

- Microbial ecosystems might create microhabitats within the crater.

The key question is resilience. If sharks can withstand rapid chemical fluctuations near a shark volcano, does this imply greater adaptability to ocean acidification linked to climate change?

Researchers have not yet established definitive answers. However, the site offers a unique testing ground for marine stress tolerance.

Monitoring Kavachi Volcano Sharks Through Satellite and Fieldwork

Field research at submarine volcanoes poses logistical challenges. Remote location, unstable conditions and eruption unpredictability limit direct observation.

Satellite monitoring, such as NASA’s Landsat imagery, provides consistent data without physical risk. Thermal signatures and plume dispersal patterns help scientists estimate eruption intensity.

Future expeditions may deploy autonomous underwater vehicles to examine how sharkcano ecosystems respond to eruptive cycles.

Long-term data collection will clarify whether volcano sharks reside permanently within the crater or cycle through periodically.

Broader Scientific and Policy Implications

Kavachi’s shark volcano underscores broader themes in marine science:

- Extreme ecosystem resilience

- Rapid environmental adaptation

- Interaction between geology and biology

- Climate-linked ocean chemistry shifts

As policymakers consider marine conservation frameworks, understanding adaptive capacity becomes increasingly relevant. If some species exhibit resilience to volcanic acidity, that insight may inform predictive models.

However, scientists caution against overgeneralization. Conditions at Kavachi are localized and episodic, not identical to gradual global ocean acidification.

Public Fascination Versus Scientific Evidence

The idea of sharks circling an erupting volcano naturally captures imagination. Terms like volcano sharks and sharkano reinforce dramatic imagery.

Yet the phenomenon is grounded in documented observation and peer-reviewed research published in Oceanography in 2016.

The environment remains hazardous. Eruptions can alter conditions rapidly. The sharks’ presence does not imply immunity to volcanic forces.

Instead, the site represents a rare convergence of geology and marine ecology.

A Living Laboratory Beneath the Pacific

The recent eruption of Kavachi confirms that the sharkcano remains active. Satellite imagery demonstrates ongoing volcanic discharge, while past expeditions verify that volcano sharks inhabit its crater.

Kavachi volcano sharks challenge assumptions about marine survival in extreme habitats. Their presence in hot, acidic waters suggests unexpected resilience.

For scientists, the shark volcano is not merely spectacle. It is a dynamic laboratory offering insights into adaptation, ecosystem recovery and geophysical processes.

As monitoring continues, Kavachi will remain a focal point for understanding how life responds to planetary extremes.

The volcano sharks of the southwest Pacific stand as evidence that even in volatile environments, ecological persistence can endure.