The distinctive Habsburg jaw — often described as the habsburg chin, hapsburg jaw or even the “inbred chin” — was most likely the result of sustained intermarriage within the Habsburg dynasty. A 2019 scientific study concluded that the prominence of the habsburg jawline directly correlated with measurable levels of inbreeding among Spanish Habsburg rulers. In simple terms, the more genetically isolated the monarch, the more pronounced the facial traits.

This conclusion was not based on legend or caricature. It emerged from systematic genetic analysis combined with historical portrait evaluation. The findings offer insight into how political strategy, intended to preserve power, produced unintended biological consequences.

The Habsburgs’ Marriage Strategy and the Origins of the Habsburg Jaw

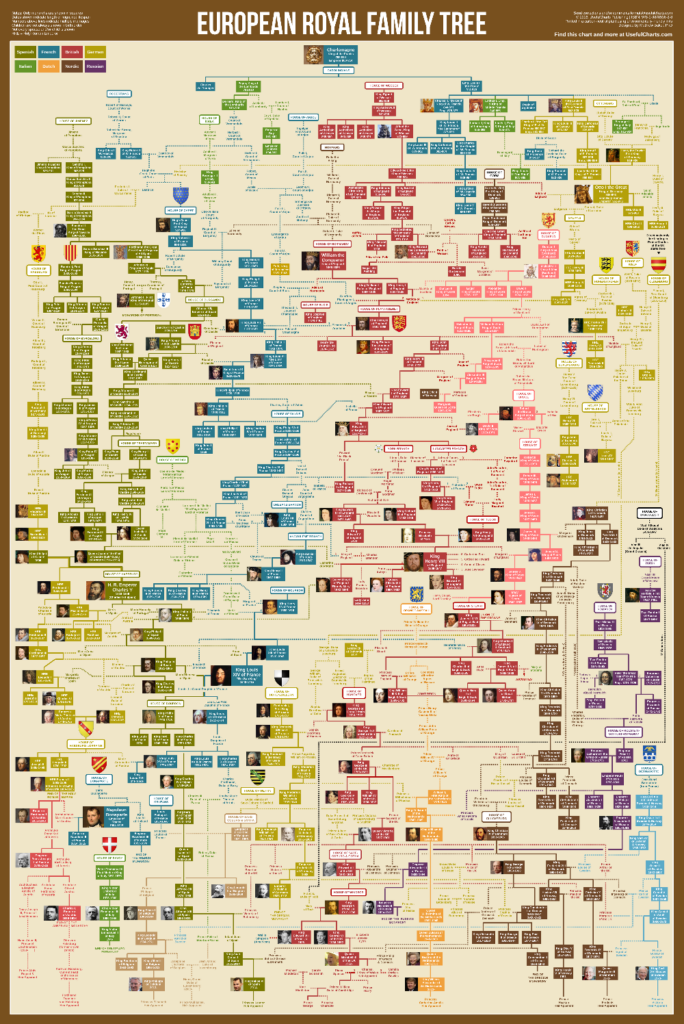

The Habsburg dynasty ruled vast territories across Europe, from Austria and Germany to Spain and Portugal. Their political approach relied heavily on strategic marriages within close family lines. Such unions consolidated territory and influence but narrowed the genetic pool.

Over generations, observers noted recurring facial features: a protruding lower jaw, elongated face, thick lower lip and nasal prominence. This became widely known as the habsburg jaw or habsburgs jaw. In contemporary language, some described it as the hapsburg chin.

While royal portraits may exaggerate traits, the repetition across multiple generations suggested a hereditary pattern. The new research sought to test whether this pattern aligned with inbreeding levels.

Spanish Habsburgs: A Two-Century Case Study

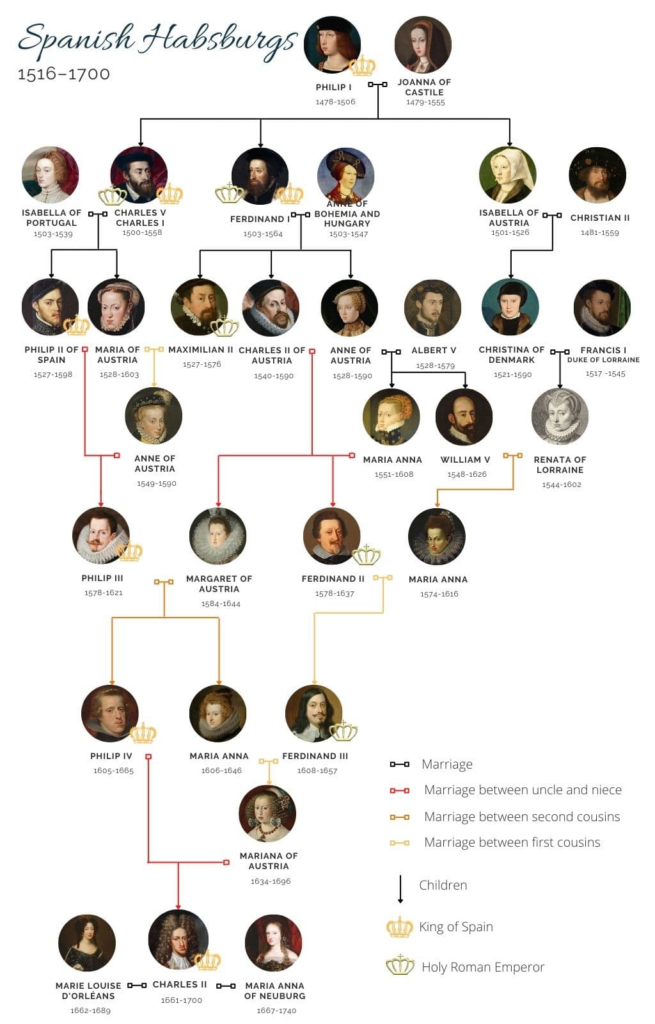

The study focused on 15 members of the Spanish Habsburg branch. This line began when Philip I married Joan of Castile in 1496. The Spanish Habsburg reign lasted nearly 200 years, ending in 1700 with Charles II.

Charles II, who died at age 38 without an heir, had long been considered an example of extreme dynastic inbreeding. His physical and neurological conditions were well documented. The research examined whether his pronounced habsburg chin reflected quantifiable genetic concentration.

Scientists reconstructed a detailed family tree covering more than 20 generations. They calculated each monarch’s inbreeding coefficient — a measure of how genetically similar their parents were.

Understanding the Inbreeding Coefficient Behind the Habsburg Chin

The average inbreeding coefficient among the studied Spanish Habsburgs was 0.093. This means roughly 9 percent of their gene pairs were identical due to shared ancestry.

For comparison:

Table: Inbreeding Coefficient Comparison

Relationship Type | Inbreeding Coefficient

First cousins | 0.0625

Third cousins | 0.004

Average Spanish Habsburg | 0.093

Charles II | 0.25

Charles II’s coefficient of 0.25 is equivalent to the child of siblings. His parents were uncle and niece, but their own inbreeding amplified the effect. This level significantly increases the probability that recessive traits — including an inbred chin — will manifest.

Medical Assessment of the Habsburg Jawline

To ensure objectivity, researchers consulted maxillofacial surgeons. They evaluated photorealistic portraits painted by artists such as Diego Velázquez and Juan Carreño de Miranda.

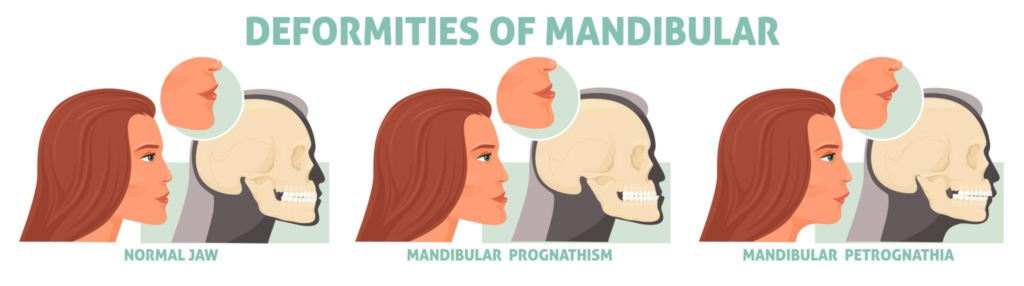

Surgeons scored each royal for features associated with mandibular prognathism (MP), which describes a protruding lower jaw, and maxillary deficiency, a recessed midface.

The results showed that individuals with higher inbreeding coefficients displayed stronger markers of the habsburg jawline. Statistical analysis indicated that differences in inbreeding explained about 22 percent of the variation in severity of the habsburg jaw.

This finding supports the hypothesis that a recessive genetic trait caused the habsburg chin to become more pronounced over time.

Charles I, Philip IV and Charles II: Visible Progression of the Habsburg Jaw

Three rulers exhibited particularly strong features:

- Charles I of Spain (Holy Roman Emperor Charles V)

- Philip IV

- Charles II

Each displayed five out of seven defining mandibular prognathism features.

Charles I’s inbreeding coefficient was 0.038 — relatively low for his family. Yet intermarriage intensified in later generations. By the time of Charles II, the cumulative effect became dramatic.

Historical descriptions of Charles II mention difficulty chewing because his lower jaw extended so far that upper and lower teeth did not align. Observers noted his enlarged tongue and speech difficulty.

These accounts match the clinical profile of advanced mandibular prognathism combined with possible neurological disorders.

Recessive Genes Versus Random Mutation: What Caused the Hapsburg Jaw?

The study suggests the habsburg jaw was likely driven by a recessive gene. Recessive traits require two identical copies of a gene to appear. Inbreeding increases the probability that both copies originate from the same ancestor.

Researchers acknowledged an alternate hypothesis: random genetic drift over generations. However, they concluded that this explanation was statistically unlikely given the strong correlation between inbreeding levels and facial severity.

In public health terms, this case illustrates how closed gene pools increase expression of rare recessive traits.

Broader Health Impact Beyond the Inbred Chin

The habsburg chin was only one visible outcome. Earlier genetic research from the University of Santiago de Compostela found that inbreeding reduced Habsburg offspring survival rates by up to 18 percent.

Charles II may have suffered from two rare recessive disorders. These conditions likely contributed to infertility and chronic illness.

Ironically, the very marriage strategy designed to preserve territorial power ultimately weakened the dynasty biologically. Political consolidation led to genetic contraction.

Policy Lessons from the Habsburg Jawline Case

From a governance perspective, the Habsburg experience offers structural lessons.

First, political systems that rely on hereditary concentration can generate unintended biological vulnerabilities.

Second, intermarriage among ruling elites may stabilize short-term alliances but undermine long-term sustainability.

Finally, scientific tools such as genealogical mapping and phenotype scoring allow historians to reassess long-standing assumptions with empirical evidence.

The habsburg jaw is not merely a historical curiosity. It demonstrates how governance choices intersect with biology.

The Habsburg Jaw as a Genetic Warning

The habsburg jaw, habsburg chin and related features were not simply artistic exaggerations. They reflected measurable genetic isolation within the dynasty. With an average inbreeding coefficient of 0.093 and Charles II reaching 0.25, the Spanish Habsburg line presents one of Europe’s clearest historical examples of inbreeding impact.

In Hindi terms, यह सत्ता की राजनीति और जैविक परिणामों का संगम था — a convergence of power strategy and genetic consequence.

By the time Charles II died in 1700 without an heir, the dynasty’s tightly woven family tree had come full circle. The effort to preserve authority through bloodline purity ultimately contributed to extinction.

The habsburgs jaw remains a reminder: biological diversity sustains resilience. Genetic concentration carries measurable risk.