The story of Mary and George is rooted in documented political maneuvering at the court of James I, where favor could determine national policy, wealth and survival. The new series Mary & George dramatizes the ascent of Mary Villiers and her son George Villiers, but the historical record confirms that their rise was neither accidental nor purely romantic—it was a calculated campaign that reshaped English court politics in the early 17th century.

While the series blends fact and fiction, the core dynamic remains accurate: Mary Villiers positioned her son as a royal favorite, and through him secured extraordinary influence at the Stuart court. The implications extended beyond scandal. They altered diplomatic direction, parliamentary relations and succession politics.

James I: A Monarch Shaped by Instability

To understand mary and george, one must first examine James I. Born in 1566, James inherited the Scottish throne in 1567 after his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, abdicated. His father had died under suspicious circumstances months earlier. During James’ minority, regents ruled—and many met violent ends.

In 1587, Elizabeth I ordered the execution of James’ mother. When Elizabeth died in 1603 without heirs, James succeeded her, becoming James VI of Scotland and James I of England.

His early exposure to betrayal and political violence shaped a cautious, often anxious monarch. The failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605 deepened his distrust. Such instability explains why James relied heavily on trusted male companions.

Before george and mary entered the picture, James had elevated Esmé Stewart and later Robert Carr. Both gained titles and influence. Yet court favor was volatile, and Carr’s fall created an opening.

Mary Villiers: Strategy Within Constraints

Mary Villiers was not born into wealth. Widowed and financially strained, she recognized that advancement required strategy rather than inheritance.

She invested in George’s education, sending him to France to acquire courtly polish, language skills and continental refinement. Such training distinguished him from domestic rivals.

Mary understood that in a male-dominated court, direct authority was inaccessible to women. Influence required proximity to power. George became her instrument.

This calculated approach forms the foundation of mary & george as both drama and documented history.

George Villiers’ Entry Into Court

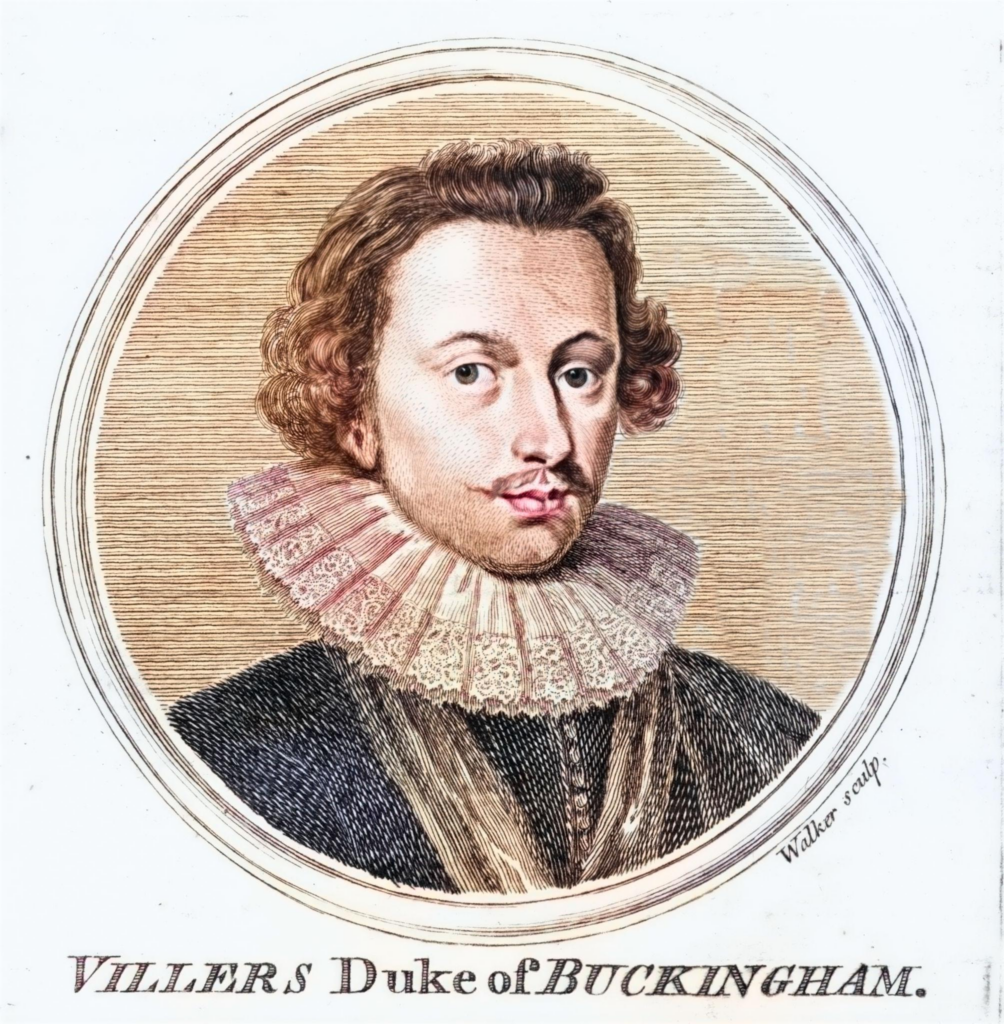

George first met James in 1614 at age 21. Contemporary accounts praised his physical grace, athletic ability and charm. His advancement was rapid.

Within nine years, George rose from cup-bearer to Duke of Buckingham. His titles included:

- Gentleman of the Bedchamber

- Master of the Horse

- Earl

- Marquess

- Lord High Admiral

Such acceleration was unprecedented. One 17th-century observer noted that no Englishman had leapt so quickly “from private gentleman to dukedom.”

The following table summarizes the trajectory.

Table: George Villiers’ Rise Under James I

Year | Position | Political Impact

1614 | Royal Cup-Bearer | Gained physical proximity to the king

1616–1617 | Gentleman of the Bedchamber | Inner-circle access

1618 | Earl and Marquess | Consolidated patronage networks

1623 | Duke of Buckingham | Dominant court influence

This concentration of authority reshaped governance at court.

The Nature of James and George’s Relationship

Debate continues regarding whether James and George shared a sexual relationship. Surviving letters reveal emotional intensity. James referred to George in affectionate terms, including “sweet child and wife.”

Public displays of affection were noted by observers. However, early modern male intimacy differed from modern definitions. Emotional bonds between men were common in elite educational and political circles.

While some historians consider a sexual dimension likely, definitive proof is absent. What remains undisputed is that their closeness translated into policy access.

Mary & George adopts a clear narrative of romantic involvement. The historical record allows interpretation but confirms influence.

Mary and George’s Influence on Policy

George’s authority extended beyond ceremonial roles. His control over royal access allowed him to shape foreign policy and patronage.

In 1623, George and Prince Charles secretly traveled to Madrid to negotiate Charles’ marriage to the Spanish Infanta Maria Anna. The mission failed, deepening anti-Spanish sentiment.

George later supported calls for war against Spain, though James favored peace. These disagreements reveal that george and mary were not merely social climbers; they were actors in geopolitical decisions.

Meanwhile, Mary herself received the title Countess of Buckingham in 1618. She attended court frequently and benefited financially from her son’s status.

Though some contemporaries depicted her as manipulative, documentation shows political acumen rather than superstition.

The Fall of Robert Carr and Consolidation of Power

Robert Carr’s conviction for involvement in the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury cleared the path for George’s dominance.

With Carr removed, James embraced English courtiers over Scottish allies. This shift altered the court’s cultural and administrative balance.

George’s ascent thus marked both personal success and a broader realignment within the Stuart regime.

The Death of James I and Accusations Against George

James I died on March 27, 1625, likely from malarial fever. George was reportedly present at his bedside.

Shortly afterward, rumors emerged alleging poisoning. A pamphlet by George Eglisham accused George of administering harmful substances. Parliament initiated impeachment proceedings, citing corruption and policy failures.

Charles I dissolved Parliament before charges could proceed.

Most historians dismiss the poisoning claim as politically motivated. However, the accusations illustrate how polarizing George had become.

Assassination and Aftermath

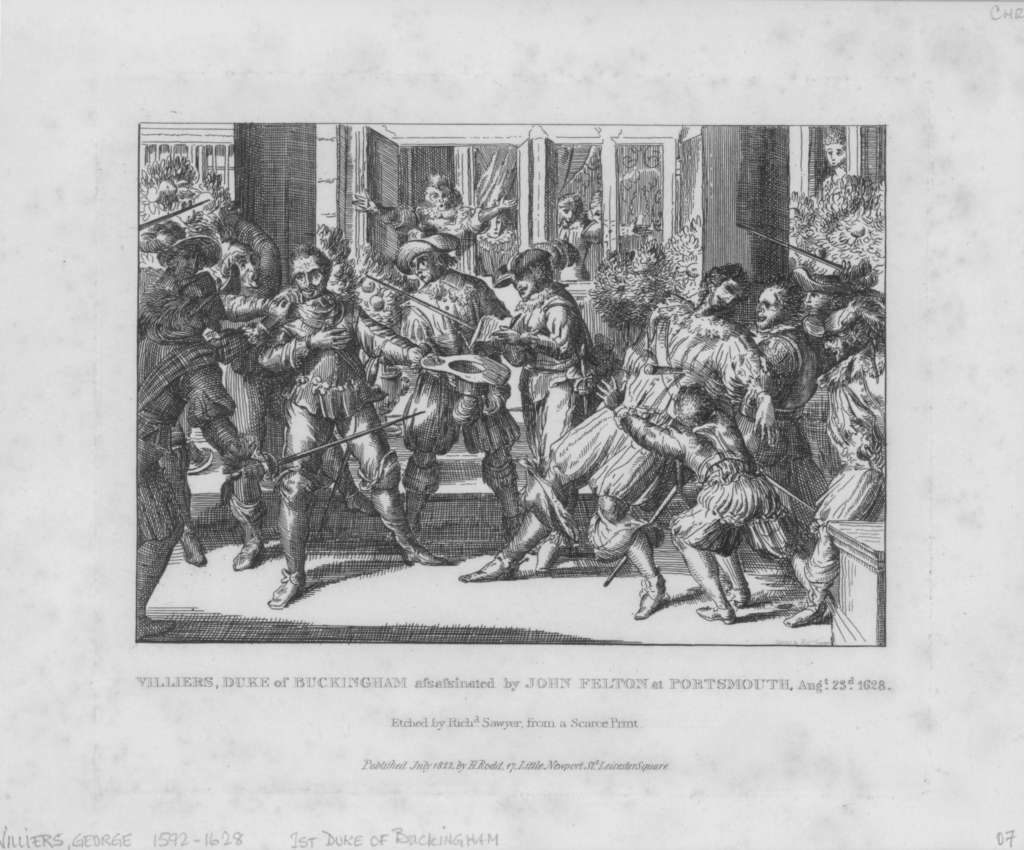

On August 23, 1628, John Felton assassinated George in Portsmouth. Public reaction was celebratory, reflecting widespread resentment.

Charles ordered a quiet burial at Westminster Abbey to prevent unrest. Mary outlived her son by nearly four years, dying in 1632.

The Villiers family, however, did not fade. George’s descendants and relatives continued serving in royal roles into the 19th and 20th centuries.

Long-Term Impact of Mary & George

The story of mary and george demonstrates how personal relationships intersect with governance structures.

Three structural consequences stand out:

- Centralization of access-based power

- Parliamentary conflict over favoritism

- Foreign policy shifts driven by court alliances

Charles I’s later execution in 1649 during the English Civil Wars reflects deeper tensions, though George’s death preceded those events.

The Villiers episode illustrates that favoritism, if unchecked by institutional balance, can destabilize governance frameworks.

Separating Drama From Documented History

Mary & George dramatizes ambition, romance and intrigue. The historical record confirms calculated advancement, emotional intensity and political leverage.

Mary Villiers recognized structural limitations and used available tools. George Villiers translated royal affection into authority. Together, george and mary altered the power equation of the Stuart court.

Their rise and fall serve as a case study in how personal networks influence public institutions. In governance terms, it underscores a recurring lesson: proximity to power is often more decisive than formal title.

The drama may embellish. The influence, however, was real.