The magnetic north pole shift toward Siberia is real, measurable and accelerating in ways scientists had not previously observed. While Earth’s magnetic poles have always moved, the recent changes in speed and direction—often described as poles shifting or even a potential polar shift—have forced experts to update global navigation models. The implications are practical, not apocalyptic: aviation, shipping, military systems and GPS calibration depend on accurate magnetic field data.

To clarify at the outset, this is not an imminent catastrophic pole shift. Instead, it is a significant geomagnetic adjustment that demands careful monitoring.

What the Magnetic North Pole Shift Actually Means

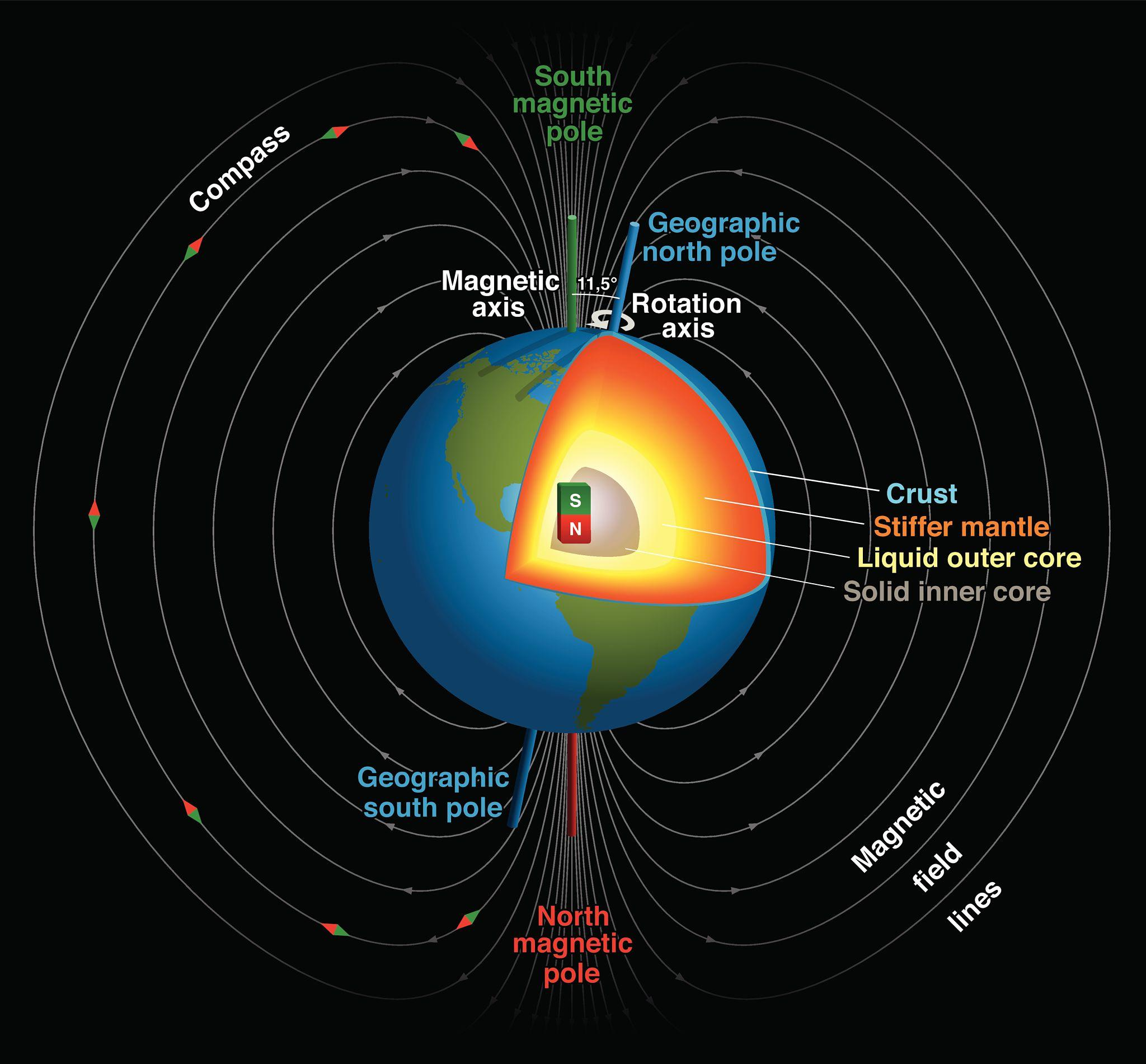

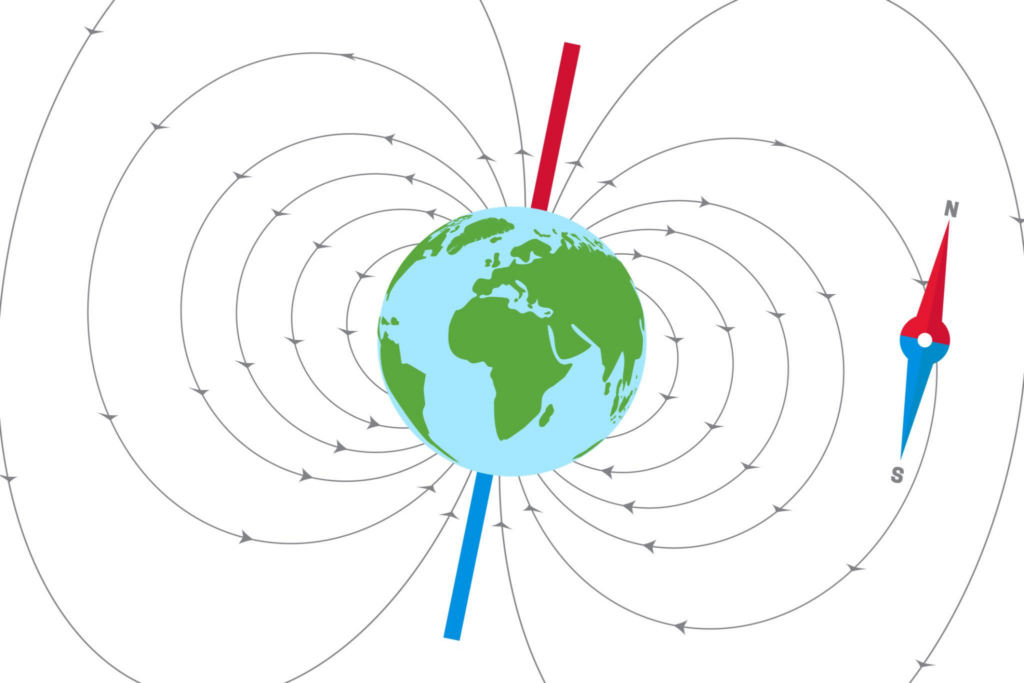

The magnetic north pole is not the same as the geographic North Pole. The geographic pole is fixed, marking where Earth’s axis meets its surface. Magnetic north, by contrast, is the point where Earth’s magnetic field lines converge.

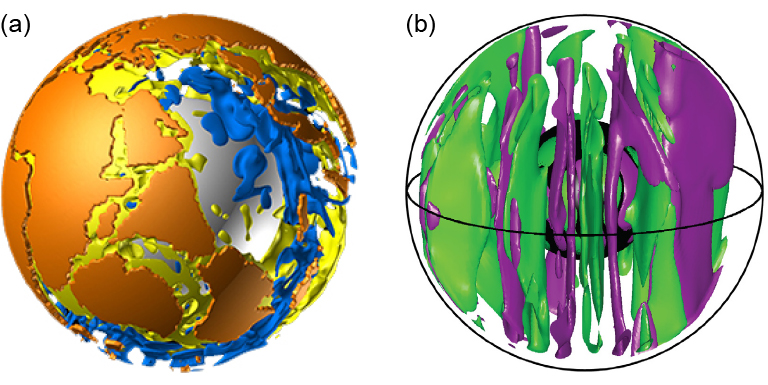

This magnetic field originates about 1,800 miles beneath the surface, in the molten outer core composed largely of iron and nickel. The churning motion of this conductive fluid generates what scientists call the geodynamo.

When core flow patterns change, the magnetic field reorganizes. As a result, the magnetic north pole shift occurs gradually over time. What has surprised researchers is the pace and direction of recent movement.

A Century of Poles Shifting: From Canada to Siberia

Since its identification in 1831 by explorer James Clark Ross, magnetic north has steadily migrated. For most of the 20th century, it drifted from northern Canada toward Russia at roughly 6 miles per year.

By the early 2000s, that rate accelerated dramatically to about 31 miles per year. Such speed raised questions about unusual core dynamics. Over the last five years, however, movement has slowed to roughly 22 miles annually.

Scientists describe this as the largest recorded deceleration following a period of rapid acceleration. The pole continues trending toward Siberia, but at a moderated pace.

The behavior is complex and non-linear, underscoring the dynamic nature of Earth’s interior.

The World Magnetic Model and Why Updates Are Critical

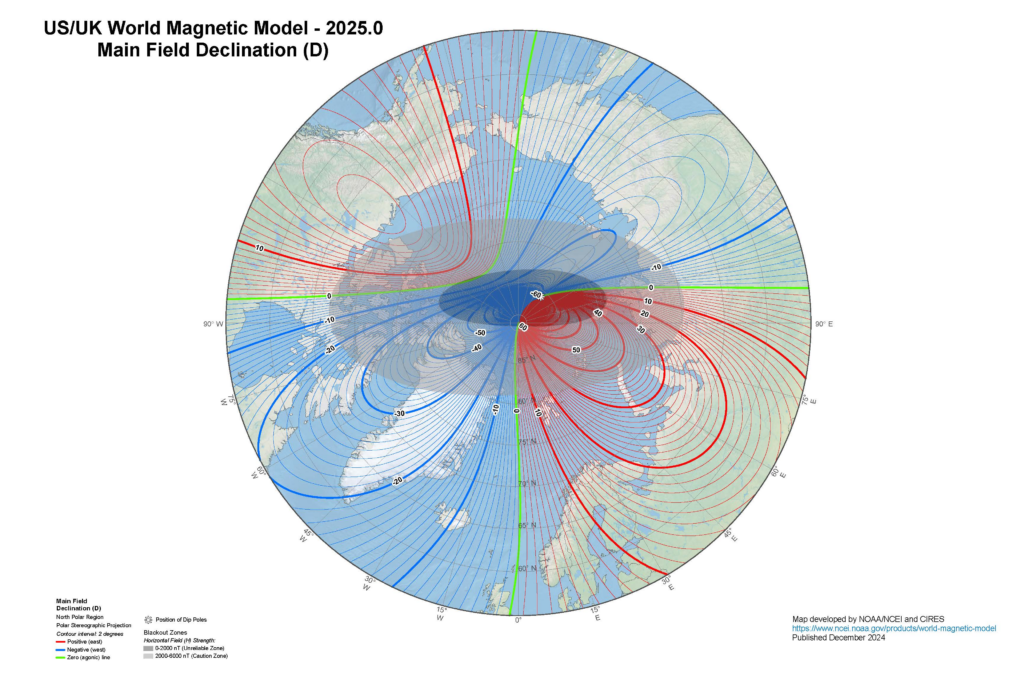

Every five years, British and American scientists release an updated World Magnetic Model (WMM). This model maps the magnetic north pole shift and predicts its near-term trajectory.

The WMM is not an academic exercise. It supports:

- Aircraft navigation systems

- Maritime shipping routes

- Military targeting and positioning

- Smartphone compass applications

- Surveying and drilling operations

If the model lags behind actual movement, navigation errors accumulate.

In 2019, the WMM was updated one year early because the magnetic north pole shift was occurring faster than forecast. The December 2024 revision reflects the latest measurements, placing magnetic north closer to Siberia than five years prior.

Why Navigation Errors Matter in Practical Terms

To illustrate the impact, scientists modeled a 5,280-mile flight from South Africa to the United Kingdom. Using outdated magnetic data, the route would end approximately 93 miles off target.

While commercial aircraft rely heavily on satellite navigation, magnetic heading remains a foundational reference. In remote regions or military contexts, precise calibration is essential.

Arnaud Chulliat of NOAA has emphasized that waiting too long to update models increases cumulative error. The WMM is essentially a forecast extrapolated from current field measurements. If the underlying field changes unexpectedly, projections degrade.

This is why the latest update includes a higher-resolution map of magnetic north than ever before.

What Is Driving the Magnetic North Pole Shift?

Researchers are still assessing the mechanisms behind the recent pole shift behavior. One leading hypothesis involves asymmetry in magnetic field strength between Canada and Siberia.

Geophysicist Ciarán Beggan notes that the magnetic field has weakened in Canada while strengthening near Siberia. The magnetic north pole shift tends to follow stronger magnetic flux concentrations.

In other words, the pole migrates toward the region exerting greater magnetic pull.

However, Earth’s magnetic field is inherently chaotic. Core convection patterns fluctuate in ways that remain difficult to model. The poles shifting reflect these deep planetary processes.

Field Weakening and the Question of a Polar Shift

Over the past two centuries, Earth’s magnetic field has weakened by about 9 percent. This decline has prompted public discussion about a potential polar shift, meaning a complete geomagnetic reversal in which north and south magnetic poles swap positions.

Such reversals have occurred many times in Earth’s history. The last one took place approximately 780,000 years ago.

However, experts caution against alarmist interpretations. A full pole shift is not imminent. Geomagnetic reversals unfold over thousands of years. The current magnetic north pole shift represents regional rebalancing rather than a global polarity flip.

Table: Key Magnetic Field Indicators

Indicator | Measurement | Context

Century-scale field weakening | ~9% | Observed over 200 years

Peak drift speed (early 2000s) | 31 miles/year | Highest recorded acceleration

Current drift speed | ~22 miles/year | Recent deceleration

Last geomagnetic reversal | ~780,000 years ago | Geological timescale event

These figures provide perspective. While change is measurable, it remains within historical precedent.

Scientific Uncertainty and Core Dynamics

William Brown of the British Geological Survey has described current magnetic behavior as unprecedented in the observational record. That does not imply instability, but it does signal complex fluid motion within the outer core.

The geodynamo is governed by heat transfer, convection currents and rotational forces. Small shifts in these flows can alter magnetic intensity and orientation at the surface.

Scientists rely on satellite missions and ground observatories to refine models. Continuous data allows better forecasting, but prediction remains probabilistic rather than deterministic.

In governance terms, this reflects the broader principle of adaptive monitoring: systems must be updated as conditions evolve.

Implications for Infrastructure and Policy

Though often framed as a geophysical curiosity, the magnetic north pole shift has policy implications.

Critical sectors affected include:

- Aviation route calibration

- Defense navigation systems

- Arctic shipping corridors

- Energy exploration drilling

- Emergency response positioning

In Arctic regions, where new sea routes are opening due to climate change, accurate magnetic mapping is increasingly vital.

International cooperation between agencies such as NOAA and the British Geological Survey ensures consistent standards. Regular WMM updates represent a preventive governance tool rather than a reactive fix.

Is a Catastrophic Pole Shift Imminent?

Public interest in poles shifting often intersects with doomsday narratives. Scientific consensus does not support such interpretations.

A geomagnetic reversal would weaken the field temporarily, but geological records show no mass extinction directly tied to past reversals. Life persisted through previous polar shift events.

Current evidence indicates ongoing field weakening and directional change, but not immediate polarity reversal.

The focus remains on incremental adaptation, not crisis response.

Conclusion: Monitoring Change, Not Predicting Disaster

The magnetic north pole shift toward Siberia reflects natural variations in Earth’s outer core dynamics. The poles shifting are measurable and significant for navigation, yet they do not signal imminent global upheaval.

Through the World Magnetic Model, scientists maintain updated maps that safeguard aviation, maritime operations and defense systems. The 2024 update, with enhanced resolution, reduces navigational risk.

In summary, the present pole shift is a technical challenge rather than a planetary emergency. Continued monitoring, data transparency and timely model revisions remain the appropriate response.

Earth’s magnetic field has always evolved. The task now is to ensure that infrastructure evolves with it.